Men Act and Women Appear : The binary of men and women figures in the nude tradition of European oil paintings

|

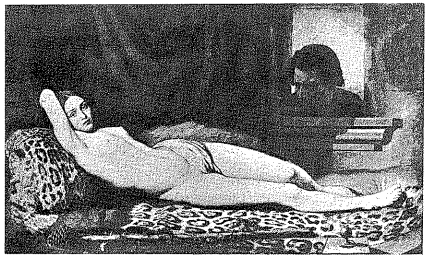

Nude Girl on a Panther Skin by Félix Trutat |

Looking through the lenses of the socio-political ideas of the

modern world, we see that many of these paintings which are highly popular

speak of much greater insights than just metaphorical meanings or the artists’

skills. If studied carefully, we observe that these nude figures are mostly of

females who either do something of trivial value, or they simply exist. The

faces and bodies of these women are nothing more than ordinary and are

portrayed through a common man’s eyes. What is remarkable in these paintings is

that the frequency of appearance of the women in their naked form is quite

higher than the appearance of men in the same way. Added to this, there is also

a stark difference in how the body movements or facial expressions of these

women figures are painted from how the same are painted of the men. These

factors, which would otherwise escape the common eye are studied in great detail

in the BBC documentary, later turned into a book, called Ways of Seeing (1972)

by art critic John Berger. It is in this book that Berger says “Men act and

women appear”. If some of these European nude paintings are looked at carefully

from Berger’s point of view, we get to know why this is accurate.

When these are compared to female nude paintings, for example, Félix Trutat's Nude Girl on a Panther Skin (1844), the stark difference is visible to the naked eye. The figure of the woman, although casual in gesture like the formerly mentioned nude of David, lacks the element of assertion. It is a docile figure, with an expression of expectation of something to happen to or around her. The obscure face of a man towards the right represents a voyeur but the woman seems quite reluctant of their presence, or maybe simply unaware. The contrast between Michelangelo's David and Trutat's painting can be explained in terms of the differential treatment of the two sexes that exists on the canvas.

The appearance of women in such ways of passivity evolved over the centuries. The trend in the female nude has been an ever-recurring subject in this category of European oil paintings from quite ancient times. The first paintings of this nude tradition were mostly of Adam and Eve. These paintings portray the appearance of women and the action of men in a non-parallel way. For example, the early 15th century painting Fall and Expulsion from Paradise by Pol de Limbourg is a classic example of how women have been portrayed in paintings since the beginning of time. In this painting, the story of Genesis is told through painted nude figures of Adam and Eve; God punishes Eve for touching the forbidden fruit by greatly multiplying her sorrow through conception and birth, and by making her subordinate to Adam, who was on the other hand made to rule the world. The submission and dominance are made clearly visible in how the nude figures of the men and women, in this case, Adam and Eve, have been formed and placed by the painter.

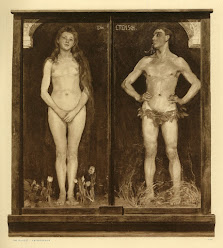

Fall and Expulsion from Paradise by Pol de Limbourg, Adam and Eve by Mabusa)

From the stance of action and inaction, when The Couple is studied carefully, it appears very obvious that Eve is uncomfortable in her own skin. She stands with her hands on her genitalia and her eyes are focused on something distant that is neither the spectator nor her counterpart Adam. Adam on the other hand has a very upright, comfortable posture and he also looks straight at Eve. His appearance again shows a promise of later action as was in the case of David. Both the figures are conscious of their nudity, yet the factor of shame is reflected only through Eve. This shows how nakedness is a perception. It is quite definitive of how a body is represented and how a spectator sees the body.

Susannah and the Elders by Tintoretto)

It is also noticeable that most of the women subjects in these paintings pay very little attention to their counterparts, irrespective of their role as lovers, voyeurs, or sexual partners. If we take a look at Bacchus, Ceres and Cupid (1605) by Von Aachen, we see this quite distinctly. This painting has the presence of a male lover, yet the woman looks directly at the spectator even while facing him. To quote Berger, “But the woman’s attention is very rarely directed towards him. Often she looks away from him or she looks out of the picture towards the one who considers himself her true lover – the spectator-owner.” This dynamic of the subject with the spectator depicts how the woman has after all no true contribution to the moment captured but her only value is in seducing the one who sees her. This factor is also somewhat present in Susannah’s paintings and shall continue to appear in the paintings discussed in the following stanzas.

After this came the factor of judgment. It was an addition to the element of shame in the European nude art tradition. As we see in Rubens’ The Judgment of Paris (1636), there is again the concept of inaction portrayed through the three Greek Goddesses Hera, Aphrodite, and Venus, who stand naked and let themselves be judged on their beauty by the armor-clad Greek hero Paris, who portrays action through his task of judgment. As Berger says “The prize is to be owned by a judge – that is to be available for him.” The way Paris looks at the women to choose the most beautiful as per general beauty standards certainly mirrors the way the spectator shall look at them. It is important to notice that the woman on the extreme right looks directly at the spectator which adds to the essence of breaking the fourth wall. This was also the case in Susannah’s paintings and the direct eye contact of these women with the spectator is meant to depict that the women ask to be looked at, to be watched, and judged by us. This creates a merge between the inside and the outside, as the spectator’s presence dissolves into the frame itself. This painting again proves that the motive of the man (Paris), is to act out something on the women (judge them), while the motive of these women is simply to be acted upon (judged) by the man.

Nell Gwynne by Lely, Allegory of Time and Love by Bronzineo)

Berger discusses all the above-mentioned paintings with respect to non-European paintings of the same age. The difference in the portrayal of women's nudes is clearly visible as the women in these paintings seem to serve their nakedness for their own desire. They are engaged in particular moments and very much part of an action. They primarily serve themselves with their nudity unlike the women in European paintings where they serve submission and docility in naked forms to the male subjects and the spectator. This also brings us to the factor that the action in men that Berger refers to not just encompasses the action of the male subjects in the painting but also of the onlooking spectator. If we take the example of Lely’s painting Nell Gwynne (1675), secretly commissioned by Charles the Second, we can understand the concept of submission to the spectator’s eyes clearly. The figures are primarily Venus and Cupid, but it is said to be painted on one of the King’s mistresses. Berger says, “It is a highly typical image of the tradition. . .It shows her passively looking at the spectator staring at her naked.” This is in fact true as we see that the only action the woman exhibits is in her submission, which was, in reality, the submission of the mistress to the painter and the patron. Even the child portrays a role of action as his posture invokes child-like impatience, while the woman simply lays and allows to be looked at. It is important to notice that along with the child who looks directly at her covered genitals, it is also the spectator who looks at the same with a similar look of longing. The woman has a jarringly direct look at the spectator which proves she has nothing to do with her sexuality and is completely possessed by the male figure, which is explicitly absent in the painting.

The narrative brings us to another point that in most of these European oil paintings, the principal protagonist is never painted. He is always presumed to be a man since the subject precisely entertains the male gaze. This is excellently evident in another version of Cupid and Venus’ painting called Allegory of Time and Love (1515-20) by Agnolo Bronzino. The posture of Venus in the painting has no relation whatsoever to the fact that she is being kissed by Cupid. Her posture has nothing to do with the act of pleasure that she may indulge in. Her body is arranged in such a way that it faces the one who is standing in front of her and looking at her. This is quite an abstract subject position and her sole purpose of the display is to satisfy the spectator’s sexual desires. The presence of Cupid and his action of touching and kissing the naked body of Venus simply aims to induce sexual competition between him and the spectator. In the words of Berger, “Women are there to feed an appetite, not to have any of their own.” Hence, both the purposes of the naked male and the female are solved, which is, to act and to appear, respectively.

Thus, we see how European oil paintings have portrayed women over the ages. In the process of being the main subject of these nude artworks, the woman figure ended up being an object to be looked at, to be touched, to be derived pleasure from. Her docility as shown in most of these paintings comes to light in plain eyes because of the contrast in the assertive male figures in the same frame beside her. The masculine-feminine binary persists even today in all forms of media and art, but it is on us how we perceive them as spectators. The statement “Men act and women appear” can be understood in no better way than by studying these paintings. To conclude with Berger’s words with respect to this nude tradition, “Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. . .The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object – and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.”

Comments

Post a Comment