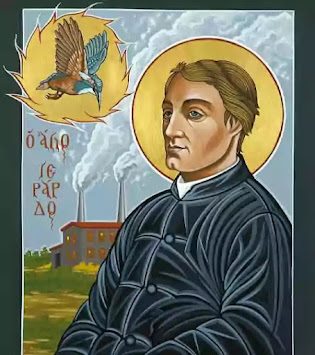

The 'terrible sonnets' : Poetry as a form of Therapy in Modernist Poet Gerard Manley Hopkins

The 19th and 20th-century movement of modernism in literature brought into light refreshing aspects of poetry, novels, and plays at the forefront. Gerard Manley Hopkins, although not an explicitly modernist writer, was a poet of the late 19th century. His poems are related to this time because his works were published in the 1920s only after his death. In his life full of emotional distress, conflicts with faith, and issues of clinical depression, Hopkins made sure to resort to art and poetry as a means of escape. “Depression” and “therapy” were big words for the time when Hopkins was writing, but by the 20th century, when his poems were published as a part of the modernist movement, these issues were eventually appearing more in the popular context. When analyzed closely, many of Hopkins’ poems suggest his struggle with terrible depression and how it is exhibited the most in six of his poems collectively called the ‘Terrible Sonnets’. Written in 1885-86, these sonnets were discovered after his death and published after the 1920s. As the name suggests, “Terrible” does not refer to the quality of the sonnets being poor but rather the reflection of the phase in his life which was absolutely terrible for him to survive. They speak of great physical and metaphysical terrors. His poems were his only suffice during these times of darkness and pretty much his only means of therapy.

When

Hopkins wrote the ‘Terrible Sonnets’, he was a Jesuit priest and a professor at

the Royal University of Dublin. As brilliant as he was as a student, his

creativity stayed constant throughout his life even after several forces of

obstruction. His greatest tragedy was probably in the fact that he was vowed to

never write again after converting to Catholicism. He even had to burn away

many of his poems after becoming a Catholic priest from an Anglican. The grief

and agony that arises in him in the eventual years are expressed through most of

his sonnets, one of them being ‘To Seem a Stranger’:

I am in Ireland now; now I am at a thírd

Remove. Not but in all removes I can

Kind love both give and get. Only what word

Wisest my heart breeds dark heaven’s baffling ban

Bars or hell’s spell thwarts. This to hoard

unheard,

Heard unheeded, leaves me a lonely began.

He gives in to the layers of estrangement he has been feeling for his

family, his country, and his faith due to his conversion and calls himself a

hoarder but never the one who is heard. There is as if a ‘ban’ on his power of

speech and creativity since he can neither write widely nor get published. It

is as if he cannot tell people what he has to say and that pains him. He can

only write for himself and a few close friends but never for the world to hear.

His alienation is aggravated when he could find no purpose or joy in the

stagnated life of a teacher at the university where he would spend days only

marking examination papers. Unlike his success at being a brilliant student at

Oxford, he could not succeed at being a brilliant teacher at the Royal

University.

As studies claim, depression symptoms are seen in people’s leaning

towards self-loathing. Hopkins’ symptoms as found through his letters and

journals were nothing different. One of his known friends called Robert

Bridges served companionship to Hopkins for many years. He was also the one

who took the effort of publishing most of Hopkins’ poems after his death. In a number

of letters exchanged between them, Hopkins’ words convey his absolute state of

distress. In one he says “AND WHAT DOES ANYTHING AT ALL MATTER?” which gives a

sense of suicidal tendency in the poet. These tendencies are also reflected in

the poem ‘No Worst There Is None’:

O the mind,

mind has mountains; cliffs of fall

Frightful,

sheer, no-man-fathomed. Hold them cheap

May who ne'er

hung there. Nor does long our small

Durance deal

with that steep or deep. Here! creep,

Wretch, under

a comfort serves in a whirlwind: all

Life death

does end and each day dies with sleep.

He has no hesitation in claiming that he is barely holding on to his

dear life from the cliff of his mind. ‘No Worst There Is None’, as Hopkins

titles this poem, is after all a direct reference to depression. It is the

worst, and there is nothing beneath it. The depth of the abyss below and the

steepness of the cliff above is too overbearing and he never wishes this upon

any man, even the one who does not understand his pain of him. He does not wish

to stay here hanging for long and looks out for sleep, for sleep is like a

little death, and death ends it all. How he ends this poem with the metaphor of

death and sleep sends chills while reading. It is almost worthy of giving a

trigger warning for anybody who reads them through their times of depression. Yet,

Hopkins lived, with no record of attempting suicide, and it was probably his

writing that helped him through this.

The imagery of death and suicide is carried even in another poem

‘Carrion Comfort’ where the word “carrion” itself means a corpse. Hopkins’ way

of using nouns as verbs is taken into consideration here as “carrion” is used

as a verb for “comfort”. His setting of motion to nouns gives them almost a

touch of personification in a way. This was typical of Hopkins who stressed new techniques in poetry writing that did not exist before him. Using nouns as

verbs, or introducing the inscape and the instress are his and his only. The

concept of haecceity or the thingness of things is reflected in most of his

poems, especially the earlier ones like ‘When Kingfishers Catch Fire’, ‘The

Windhover’, etc. In the sonnets, this is portrayed more like the essence of

things and the self. The words he speaks are very personal to him, yet so

relatable to every other person who reads them. However, the sheer brilliance

of his poetry lies in the doubt whether he wrote these simply out of emotions,

or were these calculated conventions made to inculcate in his poetry. Looking

at the lines of ‘Carrion Comfort’, we see the persistent struggles with death,

faith and misery continued in it:

Not, I'll not,

carrion comfort, Despair, not feast on thee;

Not untwist —

slack they may be — these last strands of man

In me or, most

weary, cry I can no more. I can;

Can something,

hope, wish day come, not choose not to be.

In the first line he seems to be convincing himself to not feast on

despair, to not die for it. We see how a voice of affirmation is subtly pushing

its way through all the thoughts of hopelessness and death. He says “I can

no more” and leaves it at that without any object. He can’t what? There is

no answer to that. He is as if almost too tired to state a reason for his

despair for there are thousands of them. However, unlike ‘No Worst, There Is

None’, the suicidal thoughts do not end at an abyss but find rays of

affirmation by the poet himself. It is remarkable how he uses the word “not”

repeatedly as desperate cry to not succumb to the darkness enveloping him. Right

after he says he can’t no more, he says “I can”. It is possible to understand

how haphazardly minds work at their worst emotional state but we are our only

hopes at the end of the day and the poet knows this. To say out loud “I can”

brings a lot of strength already. The starting lines to this poem almost feel

like a personal conversation with himself.

His coping mechanism, however, like anybody else, quickly shifts to

blame, in the attempt of feeling a little better about the self. He blames God

for bringing him this dreadful situation and wonders if he is being punished.

He calls God by all sorts of ferocious names but only finds his peace when he

accepts his torment. Through the poem, we see how he changes his tone and ideas

alternatively between the octet and the sestet but it hardly feels forced or

mechanical. His words that float through the poem are the words that float

through his mind while writing it. He is candid, transparent, and vulnerable at

this stage, and these characteristics themselves bring life to the poem like nothing

else.

Another important factor that runs through all of these poems is the way

they evoke a song-like effect. The frequent stresses and minimum unstresses make the reader fill their lungs with water and be unable to release

air, much like the state of Hopkins. The poems follow a typical style called

the sprung rhythm and were meant to be read out loud to produce the complete

effect of the words Hopkins uses. His poems are filled with alliterations and

figures of onomatopoeia that bring forth the complete essence of the poet’s

feelings. Without reading out loud, Hopkins’ poems might feel incomplete.

‘Carrion Comfort’ is also an important example to understand his aspect

of struggling with faith. In the closing lines of the sestet, he accepts this

torment as God’s punishment to feel relieved, but he can’t stop questioning

whether he should be happy for himself to have gotten through this torture, or

for God who despite inflicting torture, still shows him signs of life and love.

Cheer

whom though? the hero whose heaven-handling flung me, foot trod

Me? or me that fought him? O which one?

is it each one? That night, that year

Of now done darkness I wretch lay

wrestling with (my God!) my God.

It dawns upon him suddenly that it was the faith he was

wrestling with to find faith itself. He lays awake with thoughts of death and

despair and questions the motive of God which makes him guilty as well.

‘Carrion Comfort’ talks of Hopkins’ feelings on insomniac nights, but the

feelings persist also during the day as is seen in ‘No Worst

There Is None. The great emotional stress under which he wrote ‘No Worst’ even

made his comment that the sonnet is one “written in blood”. His insomnia is

also seen vividly in ‘I Wake and Feel’ where he again states his despair in not

being able to reach out to God. His sadness is so much that he even calls a man

burning in hell to be in a better situation than him. Some lines from the poem

say:

Hours I mean years, mean life. And my

lament

Is cries countless, cries like dead letters

sent

To dearest him that lives alas! away.

“Dead letters”, as he calls his pleas to God, are as though never

received by the Lord. His countless cries of lament are only cried in the void

for nothing. He stays up for hours at night, which seems like years to him. He

talks of his spirit as sour as yeast from the amount of self-hatred he feels

for himself. This arises from the fact that depressed Christians were made to

think that they are not spiritually normal. Depression was kind of synonymous

with some demonic possession or sinful evidence. For a Christian to be depressed

is one thing, but for a Jesuit priest to contemplate life and death is another.

Christianity condemns suicide and Hopkins’ continuous struggle to cope with

finding comfort in faith for his depression, and feeling guilty for being

depressed and losing faith is extremely torturing to think of. Most

commentators say that his Jesuit vocation is his primary reason for sadness. It

took away all his creativity, his ability to think freely, and most importantly,

his freedom to write. He had to constantly struggle to meet himself as a priest

and as a poet.

However, it is writing itself that never stopped for him. Even if it is

tragic to think that he never saw himself get published, it is an immense joy

to read Hopkins as one of the major Modernist poets today. Unlike his earlier

poems that describe so vividly the sounds and aesthetics of nature, his sonnets

are completely deprived of nature and what remains is pretty much the “self”.

Through his poems, Hopkins realizes himself. His train of thoughts express

themselves in his ‘Terrible Sonnets’ and not only him, but we too, as readers,

find comfort in his words. The fragility of his voice in the words is what

strikes us the most. His experience of depression gives us a space to think

that this is normal, although it is tragic that he never got to realize that.

The saying “Literature is Therapy” is

proved quite right by Hopkins as his poems not only served as a comforter to him during his

trying times but also comfort us during navigating through the bitter phases

of life where we are full of unheard emotions that quite like the poet, find a

voice through his words.

Comments

Post a Comment